Most Resolutions Fail. Here's Why

The science of successful change and the creative process of personal growth

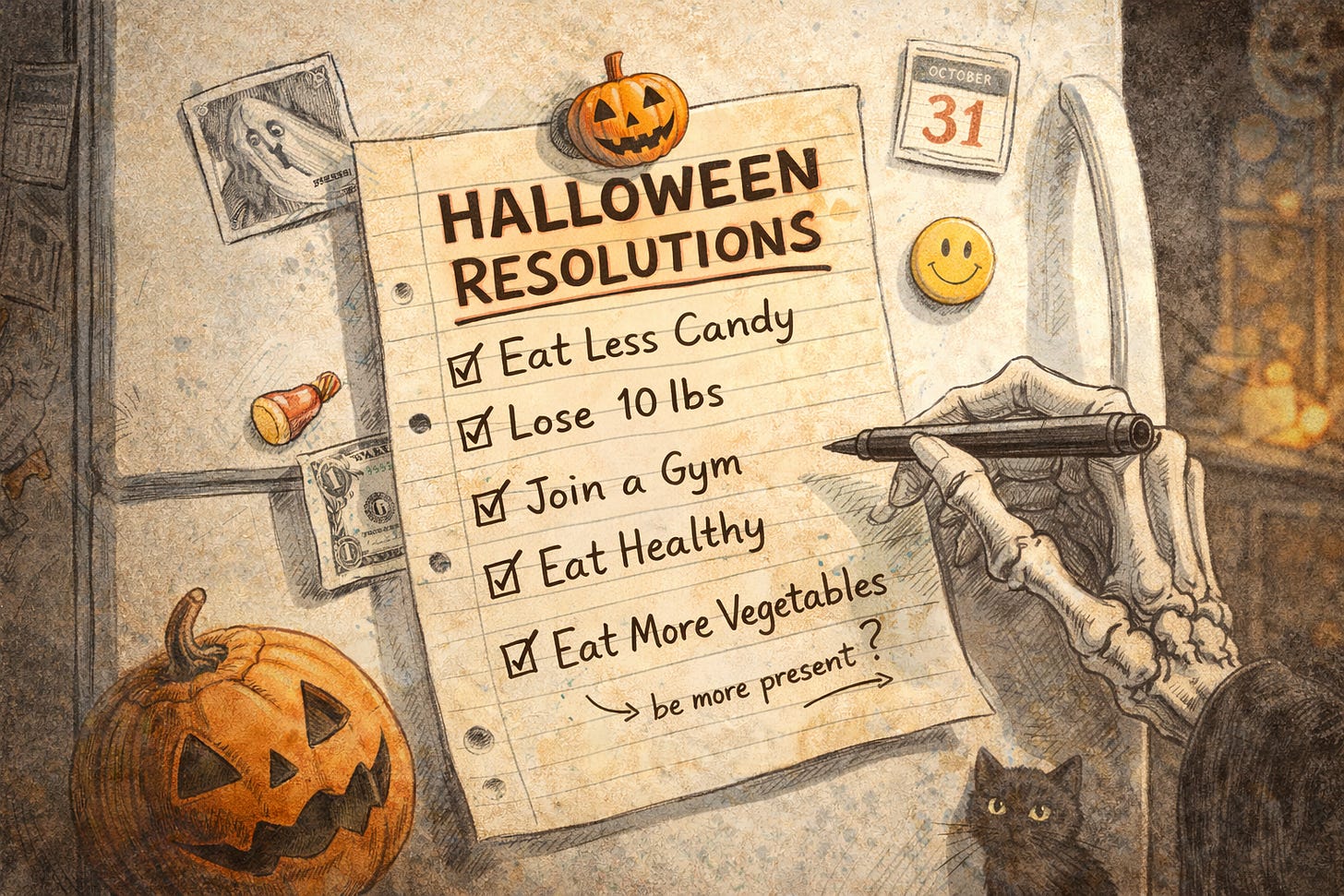

What should I change about myself next year? I’m supposed to make a resolution. But I’m stuck. After all, if I thought I needed to change myself, why wouldn’t I just go ahead and change on July 4th or on Halloween? What’s special about January?

Maybe January 1st is just an excuse to get out of doing what you should have done already. On Halloween, you’re holding your third cocktail, and you know you need to drink less. But instead of doing anything about it, you just tell yourself, “I’ll wait until January 1st and then I’ll take care of it then.” If you’re ever going to worry about drinking too much, it’s going to be the morning after the biggest drink fest of the year, New Year’s Eve. That’s why “dry-uary” exists—because of all of those resolutions. Maybe we don’t make resolutions on July 4th because “July-uary” doesn’t roll off the tongue.

No, none of that can be right. No one grabs the fifth slice of pizza and thinks, I’m going to stop doing this on December 31st, but until then, keep that pizza coming. We just think, man, this pizza tastes great. It doesn’t occur to you to reflect on your life choices. You don’t usually analyze yourself and think, I’ve been eating a lot of pizza lately.

New Year’s resolutions are not only about looking forward; they’re about reflection, about looking back. (And no, ChatGPT did not write that sentence. No GenAI was used in the making of this essay.) You don’t make a resolution to change until after you notice something about yourself that you’re not happy with.

So…what are you not that happy about? Think about the last 12 months. Did you start doing a new unhealthy thing exactly twelve months ago? Probably not. If you’ve been eating five pieces of pizza the last twelve months, you probably ate five pieces of pizza the last 24 months and the last 36 months. So why didn’t you make the resolution twelve months ago?

Maybe you did and you didn’t succeed. If so, you’re not alone. The science is pretty clear: Most resolutions fail. Studies show that 80 to 90 percent of people abandon them or don’t even get close. Only around 10-15 percent fully keep their resolutions. Actually, I feel pretty good about that. That means there’s a one in ten chance that I’ll only eat four pieces of pizza next year.

When do most people fail? If you know when it’s likely to happen, then you can get ready, you know when to watch yourself more closely. You know when you’ll need strength. Science tells us when you’re more likely to fail, By mid-January, a fourth of people have already given up. Roland Fryer’s article in the Wall Street Journal calls January 17th “Ditch New Year’s Resolution Day.” By early February, half have quit. Do they officially, publicly quit? Do people even notice that they’ve given up? Or maybe you just accidentally forget to have only two drinks. Or did you look at yourself in the mirror on January 17th and say, I’m totally fine with that belly, I’ll keep eating five pieces of pizza. Maybe your New Year’s self was simply wrong, and your February 1st self is right about life. Eating less, that’s silly talk, what was I thinking.

No, you weren’t wrong. Economists like Fryer have the answer—both resolutions and failure are all about how we balance investments and returns. It’s called “present bias.” On January 1st, we look ahead 12 months and we see that we’ve dropped twenty pounds. Great! But we don’t see how hungry we’re still going to be after two pieces of pizza. And then, on February 1st, stopping at three pieces seems like a very heavy lift. And we haven’t even lost one pound yet.

Behavioral economists have an answer for why we make resolutions on January 1st instead of making them all year round. It’s the “fresh start effect.” Research shows that after important dates, people reflect on the past and set new goals. Fryer lists “birthdays, Mondays, the start of a semester.” (He leaves out Halloween and July 4th.) It makes sense that on a birthday, you’ll reflect on the past year. In fact, I think it’s the reflection that comes first, and the resolution comes second. After all, you wouldn’t promise yourself to change if you didn’t think a change was necessary, if you weren’t unhappy with yourself.

But, sadly, the behavioral economists tell us that there’s no evidence that the motivation to change leads to durable changes in behavior. What? Read that sentence again. It says that nothing works. It says that wanting to change yourself doesn’t have any link to actually changing. That’s depressing! It seems to mean that personal change isn’t even possible.

But what about manifestation? The whole idea there is that if you think it will happen, then it will happen. What do behavioral economists say about manifestation? They would smile ruefully and say, that’s what we economists call “wishful thinking.” Actually, they have a fancier economist term for it. Fryer calls it the “intention-behavior gap”: our stated intentions only explain 25 percent to 35 percent of what we actually do. That all sounds depressing. That must be why economics is called “the dismal science.”

Science tells us how to succeed with your goals. The research shows us that yes, you can change. The key is to make resolutions, and work on them, using the latest research. Here’s how to make resolutions that work.

Set approach-oriented goals

Set a positive goal that you want to reach, like “read a book for twenty minutes before bed.” Don’t set negative goals like “stop playing games on my phone before bed.” Whenever your resolution is “stop doing something,” that’s called an avoidance goal, and science shows that these don’t work. An avoidance goal requires you to be like a traffic cop. You always have to watch yourself. Plus, it just makes you keep thinking about what you’re not supposed to be doing. You end up thinking every night, “There’s my phone on the table, but no way am I going to pick that up.” An approach goal is much more likely to work. You look at that book and think, I promised myself I would read that tonight and I’m looking forward to it.

Tweak your environment for success

Even better is to leave your phone in the kitchen every night and leave your book next to your bed. Design your space to work for you, not against you. If you resolve to eat fewer potato chips (that’s my personal kryptonite) then don’t buy any potato chips. When you’re at the grocery store, walking by the snack aisle, that’s an easy time to keep your resolution. But when the bag of chips is next to your bowl of fruit, the chips are going to win out.

Create an visible, external artifact of your resolution

Write it down. Put it on the refrigerator. Make entries in your Outlook calendar. Don’t keep it hidden up in your brain.

Research shows that external artifacts are your cognitive friend. It’s called “extended cognition.” Why not enlist the material environment in your personal goals? If it’s out in the world, it’s real. It’s no longer imaginary. You can’t “accidentally” forget about it. If you want to take a twenty-minute walk every other day, then put it in your calendar. Outlook calendar has a “recurring event” feature. You can tell it “put this event in my calendar for every Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday forever.” You don’t have to think about it again.

Resolve to change a behavior, not to reach an outcome

Instead of saying “I’m going to lose twenty pounds” say “I’m going to walk twenty minutes every other day.” Setting an endpoint, a distant goal, is too abstract. “Losing twenty pounds” doesn’t tell you what you actually need to do. But “walking twenty minutes” is concrete and specific. You can schedule it and you know right away if you didn’t do it.

Make small resolutions

Small resolutions work better than big ones. “Walk twenty minutes” is a much better resolution than “I’m going to compete in the Olympics.” Speaking for myself, a professor and an author, “Write two hours every day” is a lot better than “I’m going to write a book this year.” Momentum builds from small wins. The evidence shows that when you get quick, unambiguous feedback, your behavior changes just a tiny bit. It feels good! Then, the next day, plan for another small win. Day after day, the momentum builds, your self-confidence grows, and you’re constantly reminded of how good it feels to do the right thing.

Make specific resolutions

Specific resolutions work better than vague ones. A vague resolution is “I’m going to eat more vegetables next year.” You’re more likely to succeed with something specific, like “I’m going to eat a salad every Monday.”

Specificity works because you can’t lie to yourself. If you didn’t do it, you’ll know right away. A lot of people really need black and white before they can change. A lot of people don’t do well with gray when it comes to personal change. It’s because when you’re in the gray space, it’s human nature to gravitate toward doing whatever thing feels good in the moment.

Plan for small failures

You’re going to fail occasionally. Maybe a lot. It’s human nature. Don’t let yourself give up just because you failed yesterday. One failure doesn’t mean you should give up on your resolution for the rest of the year. I always wondered about the statistic that by February, fifty percent of people have given up already. I wonder, why would you give up just because you struggled in January? Of course you’ll struggle in January. That’s the whole reason you need to make a resolution. That’s the reason you didn’t start doing it on Halloween.

Don’t think of failure as an indictment of your personality and your willpower. That becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. This is one of the most important insights of manifestation: If you think you’ll fail, then you will fail. But when you have a growth mindset, you believe that change is possible, and research shows that you are indeed more likely to reach your goals.

The key is to incorporate small failures into your plan. Design your environment and your schedule so that if you fail once, it doesn’t derail your entire year. I’m hesitant to give you examples, because you might get too lenient on yourself, but what about something like “if I don’t read twenty minutes one night, I’ll read more the next night.” That acknowledges that some nights, you might not get to the book, or maybe you forgot to do the Wordle for today.

Personal growth is a creative process

I’m a creativity researcher and I specialize in the creative process. Creativity isn’t only an outcome; it’s a process, a way of living and working. How does creativity flow, from the starting point of noticing a problem to the ending point of making something new and original? My research shows that there are endless twists and turns. I call them zig zags. Creativity is an iterative process, not a linear process. It’s not about having one big idea at the beginning and then executing and delivering on that idea. In an effective creative process, you don’t know where you’re going. You’re exploring, you’re looking, you’re trying to find your way. It feels like a mess when you’re in it, but trust the mess, trust the process.

In the zig zag process of creativity, you have constant small sparks of ideas. Don’t expect to have just one big idea that solves your problem all at once. If you keep having small, tiny ideas, they keep driving the creative process forward. If you keep living a creative life, if you keep open, and aware, and keep exploring, those small ideas will keep coming. You’ll end up with something great.

It’s the same with personal growth and change. Creativity isn’t about flashes of insight in the bathtub. The creative life is a life of small ideas, daily practices, and creative mindsets. Creative breakthroughs emerge from a process, from steady awareness and mindfulness, not from divine inspiration.

So, why January 1st?

When I started writing this post, I was going to make it be a summary of my latest podcast episode, The True Story About New Year’s Resolutions. In that episode, I tell you when humanity started making resolutions and how we got where we are today. It starts in Ancient Babylon (a lot of historic stories start with Babylon). Then I move through the Roman Empire (a lot of historic stories do that, too) and Christianity in the Middle Ages and the Reformation (once again, a lot of stories do that). I end the episode by describing how modern media and consumer culture have gotten us where we are today. Come to think of it, that’s the same history of pretty much everything, including my podcast episode about the origins of the Christmas holiday, Where Did Santa Clause Come From. Look for a Halloween episode next October.

The origin of New Year’s resolutions is a fascinating story and I hope you listen to the episode!

But once I started writing this Substack post, the story got away from me. I ended up writing this post about the science of making resolutions. And, now that I’m done typing, I realize that maybe I should have done a podcast about this.

Resolved: Next year, I’ll do more podcasts with practical advice and less podcasts with obscure historical facts. I’m going to practice what I preach and I’ll make a resolution that’s more likely to succeed. Here’s what the science says:

Set approach-oriented goals. Don’t say “I’m not going to do as many historical origin stories that start with Babylon.” Instead, “I’m going to do more personal advice episodes.”

Be specific. Instead of a vague goal like “Do more personal advice episodes,” I should be specific. For example: Do 20-minute podcasts that each have five useful tips. Do a podcast about how to make friends.

Make small resolutions. Don’t say “I’m going to completely reinvent my entire podcast show”; that’s too big and too vague. And I actually really like my podcast! I’m thinking about small tweaks, not complete reinvention.

What do you think I should do with my podcast next year? Let me know what you think in the comments. Feel free to give me your ideas for episodes where the science of creativity can help you in your personal and professional life.

This Substack essay is free but it took a lot of time to write. Please consider a paid subscription. I guarantee that no artificial intelligence was used in the creation of this essay. If it had been, my prompt was going to be “Write a Substack post based on my podcast episode about the origins of New Year’s resolutions.” In fact, I’ll be honest—at first, I did exactly that. But the ChatGPT essay was horrible. It had no merit whatsoever. I’m happy to say that what I wrote here is better than what ChatGPT came up with. But it took a lot longer to write. Your paid subscription would really help me keep writing in the next year!

Creativity is just that - creating. That does not mean that every creation is a light bulb moment, but the fact that you take the time to create, whether the creation is great or terrible, is a building block/a learning moment. Taking the time to create means that at some point, whether now or in the future, you will have created something that you are proud of. Keep a journal of your creations, just like a song writer keeps a journal of snippets that eventually get woven together and edited to make a wonderful piece. Do it!

In 2026, I'm gonna read the three books of yours that I have but never got 'round to (zigzag, learning to see, and explaining creativity). And I am going to get paint all over myself.