Conlangs, Auxlangs, and Engelangs: The Art of Language

Invented languages, natural languages, and the collaborative nature of creativity

Here's a topic that's ripe for creativity research: constructed languages, or "conlangs" for short.

I learned about conlangs from David Peterson's book The Art of Language Invention. David Peterson is a conlanger—someone who creates conlangs for a living (I’m not kidding; he worked on Game of Thrones). His book was so fascinating that I wanted to read more! Then I found the super-fun book In the Land of Invented Languages by Akira Okrent. They’re both wonderful!

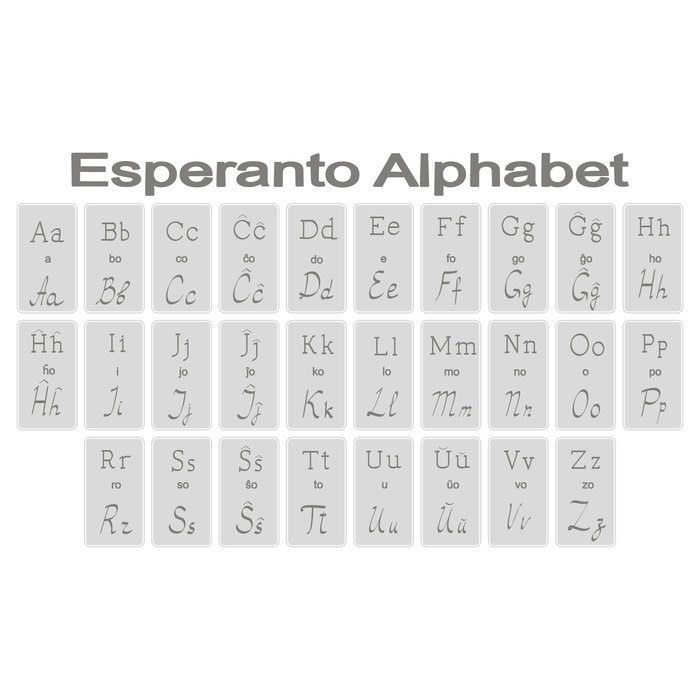

The oldest conlang that you've heard of is probably Esperanto--created in 1887 by Polish physician L. L. Zamenhof to promote international peace through mutual understanding. It's known as an "international auxiliary language" or auxlang. Esperanto wasn’t the first auxlang; it was preceded by Volapuk, created in 1879 by a German priest, Johann Schleyer.

Most conlangs were created by an author to make give their fantasy worlds depth; to make them seem more real. Some of the oldest conlangs are the ones created by J. R. R. Tolkien. He created Sindarin, the language of the Elves in his imaginary world. One of the most famous conlangs today is Klingon, from Star Trek. This one is widely known because of the hit TV comedy Big Bang Theory, where the geeky lead characters demonstrate their geek cred by speaking Klingon. I heard Klingon spoken when I was a student at MIT in the 1980s; yes, there are real geeks who really do speak Klingon! Big Bank Theory nails the geek culture that I lived in.

Peterson's book also describes Dothraki, created for Game of Thrones, which Peterson himself extended from a version originally created by novelist George Martin. Princess Leia spoke a conlang with Jabba the Hutt in Return of the Jedi. Peterson created an elvish language for the movie Thor and also worked on the Syfy channel's Defiance (creating Castithan, Irathient, and Indojisnen). Avatar used the conlang Na'vi (created by Professor Paul Frommer); The Land of the Lost used Pakuni, created by linguist Victoria Fromkin; and Dark Skies used Thhtmaa, created by linguist Matt Pearson.

Peterson's book focuses on the languages he created for movies. Linguist Doug Ball goes deeper into the historical and social background. (You can watch his TEDx talk here.) In his article “Invented Languages,” Ball discusses "engineered languages" or engelang, like Loglan, created in the 1950s by James Cooke Brown to test the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis that different languages result in different thought patterns. Other engelangs include Lojban and Laadan. Ball goes way, way, back, to the first recorded conlang, Lingua Ignota, created in the 12th century by Hildegard von Bingen. In the 17th century, conlangs were trending—it seems like every famous scholar had one, including Descartes and Leibniz.

Some conlangs are designed to have aesthetic qualities, and these are known as "artistic languages" or artlangs. My favorite conlang is Solresol, which is based in the idea that music is the universal language. The basic syllables of the language are the seven pitches of the Western diatonic scale (with pitches referred to by their French names, since this was created in 1827 by Frenchman Jean-Francois Sudre). Here's an example:

dore mifala disofare re dosiresi

The direct translation is “1SG desire beer and pastry” and then, with the words reordered, it means “I want some beer and a pastry.”

Ball poses all sorts of interesting linguistic and creativity questions. How do these languages get created? What options do creators have? Which languages are successful, and why? How do you create a lexicon and syntax? Then he asks the creativity question:

Is conlanging an art?

His answer:

Even if conlanging is to be considered an art, it seems as though it must be regarded as a niche creative endeavor, since its consumption is not straightforward.

That seems like a big hedge—so is it an art or not? Let us know what you think in the comments!

What about “regular” languages? English and Chinese? They’re called natural languages. Those haven’t been around forever, so they had to be created at some point, right? Here’s what Akira Okrent says about that, in her book In the Land of Invented Languages:

Although we like to call language mankind’s greatest invention, it wasn’t invented at all. The languages we speak were not created according to any plan or design. Who invented French? Who invented Portuguese? No one. They just happened. They arose. Someone said something a certain way, someone else picked up on it, and someone else embellished. A tendency turned into a habit, and somewhere along the way a system came to be. This is the way all natural languages are born—organically, spontaneously.

This might be just semantics, about the meanings of “invention” and “creativity,” but I would claim that the invention of a natural language is a wonderful example of creativity! It’s what I call group genius, the collective wisdom of the crowd. Natural languages emerge from a decentralized, complex system—a social network that constitutes a complex mechanism. Like all mechanisms without central control, either they devolve into chaos, or structures gradually emerge. Once a structure emerges, it crystalizes and becomes stable. These emergent stabilities include cultures, societies, and languages. This is group genius; it’s collaborative creativity.

We can learn a lot about group genius by studying the differences between natural languages and invented languages. Invented languages have an identifiable creator. Their creation is centralized, planned, and designed. Would a planned language be similar, or different, from an emergent decentralized collectively created language? There has been surprisingly little research about this amazing form of creativity. I can think of hundreds of possible doctoral dissertations about that! The research so far only scratches the surface of this fascinating creative activity.

Is conlanging an art? What do you think? Do you speak a conlang? Have you invented a conlang? Leave a comment and let us know!

Keep creating and have a great day!

Keith

To learn more:

Douglas Ball, "Constructed languages." In The Routledge handbook of language and creativity, 2015, edited by Rodney H. Jones.

Henry Hitchings, review of Peterson: "Mastering Dothraki". WSJ, October 3-4, 2015, p. C6

Arika Okrent. In the land of invented languages: Adventures in linguistic creativity, madness, and genius.

David J. Peterson, The art of language invention.

Keith Sawyer, Group Genius: The Creative Power of Collaboration.

My whole substack is on this topic exactly! In my opinion, conlangs are without a doubt an art. They are a form of self expression, and show the creators outlooks on life. I do think, however, that this definition of conlangs as an art depends on how you define art itself. Does art need to be viewed and interpreted by others to be an art, or can it be purely personal? It seems that Ball defines it as needing to be interpreted by others, as he states "its consumption is not straightforward," meaning that an audience would have to learn the conlang to interact with it, and for it to be properly considered an art.